Video Lecture

Electric Current

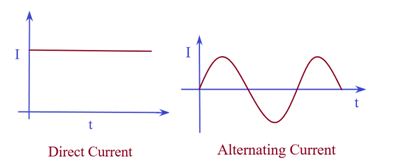

Charges in motion make an electric current.

Time rate of flow of charge through a cross-section is called electric current.

Suppose, a charge Δq passes through a given cross section Area in a short time Δt, then the average electric current is

Iav = \frac{{\Delta q}}{{\Delta t}}

More precisely, the instantaneous current at a given time t is

Iinst = \underset{{\Delta \,t\to 0}}{\mathop{{\lim }}}\,\frac{{\Delta q}}{{\Delta t}}=\frac{{dq}}{{dt}} \displaystyle n\ne 1

If the current is steady or constant (i.e., it does not change with time), then the charge q flowing through is a linear function of t (i.e. just proportional to tn, where n=1). In that case the average current and instantaneous current are same.

Whereas for a varying current where q= f(tn) where \displaystyle n\ne 1 the average current and the instantaneous currents may be different in magnitude.

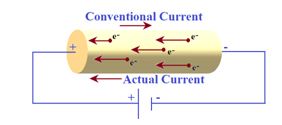

Conventionally, the direction of current is taken to be the direction of flow of positive charge, (i.e., the direction of the field).Hence this current is also called conventional current. Whereas in a metallic conductor the actual current flows through the motion of electrons that takes place opposite to the motion of positive charges and this is called actual current.

In a conductor (such as copper, aluminum, etc.) the current flows due to the motion of free electrons (negatively charged particles). Hence, the direction of electric current is opposite to the direction of flow of electrons.

In semiconductors, the current is carried by both the electrons (negative) and holes (positive). Hence, we say that in semiconductors there are two types of current carriers viz., electrons and holes. In a discharge tube, the current carriers are positive ions and negative electrons. In an electrolyte, the current flows due to the motion of both the positive ions and negative ions.

In case of semiconductors, electrolytes and discharge tubes, though the positive and the negative charge move in opposite directions, the current due to them will be in the same direction.

Furthermore, though the positive and negative charges are equal, their contributions to current are usually not the same. The heavier current -carriers move slower and their contribution to electric current is less than that of lighter ones.

I = \frac{{\Delta Q}}{{\Delta t}}=nqA\frac{{\Delta x}}{{\Delta t}}=nqvA

Current Due to Rotatory Motion of Charge

If a point charge q is moving in a circle of radius r with speed v, then its time period T = (2πr/v).

So through a given cross-section (perpendicular to motion), the current is

Current Density

Electric current may be distributed non-uniformly over the surface through which it passes. Hence, in order to characterize the current in greater detail, we introduce the concept of current density vector \vec{J} at a point, defined as follows :

(1)

The magnitude of \vec{J} is equal to the current per unit area surrounding that point and normal to the direction of charge flow. Thus,

\left| {\vec{J}} \right|=\frac{{dI}}{{dA}}

(2)

The direction of \vec{J} is the same as the direction of velocity vector \displaystyle \vec{v} of the ordered motion of positive charge-carriers.

Drift Velocity

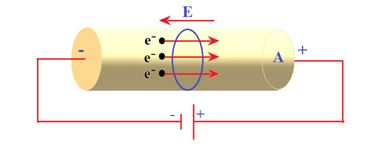

The drift velocity is the average uniform velocity acquired by free electrons inside a metal conductor by the application of an electric field which is responsible for current through it.

Free electrons, under the influence of thermal agitation, move randomly throughout the metallic conductor from one point to another in an irregular manner in all possible directions as shown in Fig. (A). However, if a source of potential difference is applied across the two ends of the conductor, the electrons gain velocities tending them to move from negative to positive side of the conductor. Average value of these velocities is termed as drift velocity. The drift velocity of the electrons is no doubt superimposed on their random velocity, but in fact this is the cause for net transportation of the charge along the conductor and hence results in a current flow.

In absence of any electric field the random motion of electrons does not contribute to any current. The number of electrons crossing any plane from left to right is equal to the number of electrons crossing from right to left (otherwise metal will not remain equipotential).

When an electric field is applied, due to electric force the path of electrons in general becomes curved instead of straight lines and electrons drift opposite to the field

Relation between drift velocity and electric field

Due to random motion, the free electrons of metal collide with positive metal ions and undergo change in direction after every collision. So, the thermal velocities are randomly distributed in all possible directions.Therefore, the average of all thermal velocities is zero

\vec{u}=\frac{{{{{\vec{u}}}_{1}}+{{{\vec{u}}}_{2}}+…..+{{{\vec{u}}}_{n}}}}{N}=zero

Here, {{\vec{u}}_{1}},\,{{\vec{u}}_{2}} , . . . , {{\vec{u}}_{n}} are the individual thermal velocities of the free electrons at any given time and N is the total number of free electrons in the conductor.

However, when some potential difference V is applied across the two ends of a conductor of length l, an electric field is set up. which is given by, E = V / l

then each free electron in the conductor experiences a force \displaystyle \vec{F}=-e\vec{E} in a direction opposite to the direction of electric field.

If m is the mass of the electron, then acceleration produced is \vec{a}=-\frac{{e\vec{E}}}{m}

At any given time, an electron has a velocity such that {{\vec{v}}_{1}}={{\vec{u}}_{1}}+\vec{a}{{\tau }_{1}} , where {{\vec{u}}_{1}} is the thermal velocity and \vec{a}{{\tau }_{1}} is the velocity acquired by the electron under the influence of the applied electric field. where t1 being the time of acceleration or time that has elapsed since the last collision.

Similarly, the velocities of the other electrons are {{\vec{v}}_{2}},\,{{\vec{v}}_{3}}…..{{\vec{v}}_{N}} , such that

{{\vec{v}}_{2}}={{\vec{u}}_{2}}+a{{\vec{\tau }}_{2}},

{{\vec{v}}_{3}}={{\vec{u}}_{3}}+\vec{a}{{\tau }_{3}}

,

.

.

.

{{\vec{v}}_{n}}={{\vec{u}}_{n}}+\vec{a}{{\tau }_{N}}

The average of all these velocities of all the free electrons in the conductor is the drift velocity .Drift velocity is defined as the velocity with which the free electrons get drifted towards the positive terminal under the influence of the externally applied electric field.

So, {{\vec{v}}_{d}}=\frac{{{{{\vec{v}}}_{1}}+{{{\vec{v}}}_{2}}+{{{\vec{v}}}_{3}}+…+{{{\vec{v}}}_{N}}}}{N}

\Rightarrow \text{ }{{\vec{v}}_{d}}=\frac{{({{{\vec{u}}}_{1}}+\vec{a}{{\tau }_{1}})+({{{\vec{u}}}_{2}}+\vec{a}{{\tau }_{2}})+….+({{{\vec{u}}}_{N}}+\vec{a}{{\tau }_{N}})}}{N}

\Rightarrow \text{ }{{\vec{v}}_{d}}=\frac{{({{{\vec{u}}}_{1}}+{{{\vec{u}}}_{2}}+….{{{\vec{u}}}_{N}})}}{N}+\vec{a}\left( {\frac{{{{\tau }_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}}+….+{{\tau }_{N}}}}{N}} \right)

But, \frac{{{{{\vec{u}}}_{1}}+{{{\vec{u}}}_{2}}+…+{{{\vec{u}}}_{N}}}}{N}=0

⇒ {{\vec{v}}_{d}}=\vec{a}\frac{{{{\tau }_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}}+….+{{\tau }_{N}}}}{N}

or, {{\vec{v}}_{d}}=\vec{a}\tau where \tau =\frac{{{{\tau }_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}}+….+{{\tau }_{N}}}}{N}

Here, tis called the relaxation time and it is defined as the average time of acceleration between two successive collisions.

Now if we put \vec{a}=-\frac{{e\vec{E}}}{m}

we get {{\vec{v}}_{d}}=-\frac{{e\vec{E}}}{m}\tau

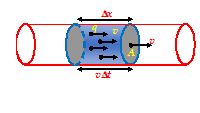

Current in a Conductor

Consider a conductor of uniform cross-sectional area S. If n is the number of free electrons per unit volume, the charge per unit volume is ne. If vdis the drift velocity, electrons move a distance vdin one second. Therefore, the volume moved in one second is vdS.

Thus, the current, \displaystyle I=\frac{{ch\arg edensity\times Volume}}{{Time}}=\frac{{(ne)\times (v{}_{d}A)}}{1}=nev{}_{d}A

J = \frac{I}{A}=ne{{v}_{d}}

or vd = \frac{J}{{ne}}

Metals (conductors) have large number of free electrons per unit volume (» 1028/m3). Therefore, the drift velocity is very small (»10-4 m/s) compared to random speed of electrons at room temperature (» 106 m/s).

Illustration

The area of cross-section, length and density of a piece of a metal of atomic mass 60 gm/mole are 10-6 m2, 1 m and 5 x 103 kg/m3 respectively. Find the number of free electrons per unit volume if every atom contributes one free electron. Also find the drift velocity of electrons in the metal when a current of 16 A passes through it. Given that Avogadro’s number NA = 6 x 1023/mole and charge on an electron e = 1.6 x 10-19 C.

Solution

According to Avogadro’s hypothesis,

\displaystyle \frac{N}{{{{N}_{A}}}}=\frac{m}{M}

so n = \displaystyle \frac{N}{V}={{N}_{A}}\frac{m}{{VM}}=\frac{{{{N}_{A}}d}}{M}

(as d = \displaystyle \frac{m}{V})

n = \displaystyle \frac{{6\times {{{10}}^{{23}}}\times \left( {5\times {{{10}}^{3}}} \right)}}{{\left( {60\times {{{10}}^{{-3}}}} \right)}} = 5 x 1028 /m3

Now as each atom contributes one electron, the number of electrons per unit volume is also the same.

J = \displaystyle \frac{I}{A}=\frac{{16}}{{{{{10}}^{{-6}}}}} = 16 x 106 A/m2

vd = \displaystyle \frac{J}{{ne}}=\frac{{16\times {{{10}}^{6}}}}{{\left( {5\times {{{10}}^{{28}}}} \right)\times \left( {1.6\times {{{10}}^{{-19}}}} \right)}}=2 x 10-3 m/s

Mobility (μ)

In a substance, although the amount of charge on a positive charge-carrier and on a negative charge–carrier may be the same, but the two types of carriers may not give equal contribution to electric current. For example, in a semiconductor, (such as Ge or Si), the two types of charge-carriers are electrons (negative) and holes (positive). When an electric field is applied, the electrons are found to drift more than the holes. We say that the mobility of electrons is more than that of holes.

Mobility (μ) of a charged particle in a substance is defined as the drift velocity per unit field applied,

m = \frac{{{{v}_{d}}}}{E}

The units of mobility are \frac{{m/\sec }}{{volt/m}} that is m2/Vs.

Illustration

The current in a wire varies with time according to the relation

i = a + bt2,

where current i is in ampere and time t is in second; a = 4A, b = 2As-1.

(a)

How many coulomb pass a cross-section of the wire in the time interval between t = 5 s and

t = 10 s ?

(b)

What constant current could transport the same charge in same time interval ?

Solution

(a)

Δq = \displaystyle \int\limits_{5}^{{10}}{{i\,\,dt}}=\int\limits_{5}^{{10}}{{\left( {4+2{{t}^{2}}} \right)\,\,dt}}

= \displaystyle \left| {4t+\frac{2}{3}{{t}^{3}}} \right|_{5}^{{10}}=4\left( {10-5} \right)+\frac{2}{3}\left( {1000-125} \right) = 603.33 C

(b)

Ie = \displaystyle \frac{{\Delta q}}{{\Delta t}}=\frac{{603.33}}{{10-5}} = 120.67 A

Illustration

In the Bohr model of hydrogen atom, the electron is pictured to rotate in a circular orbit of radius 5´10-11 m, at a speed of 2.2 x 106 m/s. What is the current associated with electron motion ?

Solution

The time taken to complete one rotation is

T = \frac{{2\pi r}}{v}

Therefore, the current is

I = \displaystyle \frac{q}{t}=\frac{e}{T}=\frac{{ev}}{{2\pi r}}=\frac{{1.6\times {{{10}}^{{-19}}}\times 2.2\times {{{10}}^{6}}}}{{2\times 3.14\times 5\times {{{10}}^{{-11}}}}} = 1.12 mA

Illustration

One end of the aluminium wire whose diameter is 2.5 mm is welded to one end of a copper wire whose diameter is 1.8mm. The composite wire carries a current I of 1.3A. What is the current density in each wire?

Solution

The current density is given by \displaystyle j=\frac{I}{A}

For Aluminium wire, \displaystyle {{A}_{{(AI)}}}=\frac{{\pi {{d}^{2}}}}{4}=\frac{\pi }{4}{{(2.5\times {{10}^{{-3}}})}^{2}}=4.91\times {{10}^{{-6}}}{{m}^{2}}

\displaystyle {{j}_{{(AI)}}}=\frac{I}{{{{A}_{{(AI)}}}}}=\frac{{1.3}}{{4.91\times {{{10}}^{{-6}}}}}=2.6\times {{10}^{5}}\text{A}{{\text{m}}^{{-2}}}=26A\,\text{c}{{\text{m}}^{{-2}}}

For copper wire, \displaystyle {{A}_{{\text{(Cu)}}}}=\frac{{\pi {{d}^{2}}}}{4}=\frac{\pi }{4}{{(1.8\times {{10}^{{-3}}})}^{2}}=2.54\times {{10}^{{-6}}}{{\text{m}}^{2}}

\displaystyle {{j}_{{\text{(Cu)}}}}=\frac{I}{{{{A}_{{\text{(Cu)}}}}}}=\frac{{1.3}}{{2.54\times {{{10}}^{{-6}}}}}=5.1\times {{10}^{5}}\text{A}{{\text{m}}^{{-2}}}=51A\,\,\text{c}{{\text{m}}^{{-2}}}

Ohm’s Law

Consider a conductor of cross section `A’. Let n be the free electron density in the conductor. And through a battery a current `I’ is made to flow in it.

We know that, I = neAvd and vd = \frac{{eE}}{m} t

\therefore \text{ }I=neA\left( {\frac{{eE}}{m}} \right)\tau

or, I=\frac{{n{{e}^{2}}AE}}{m}\tau (here E is electric field which is related to potential difference V)

we know that E=\frac{V}{L} , on putting it in the above relation of current we get

I=\left( {\frac{{n{{e}^{2}}A\tau }}{{mL}}} \right)V

Or V=\left( {\frac{{mL}}{{n{{e}^{2}}A\tau }}} \right)I

Now if we assume that in RHS all quantities written in the brackets are constant and denoting the whole bracket with a symbol `R’ then the above relation can be written as

V =RI ,(Ohm’s Law) where R=\frac{{mL}}{{n{{e}^{2}}A\tau }} and is called resistance.

Ohm’s Law

If the temperature of a conductor remains constant, then the ratio of the potential difference (or voltage) V to the current I remains constant for any conductor, which is known as resistance `R’ of the conductor.

\displaystyle \frac{V}{I} = constant = R

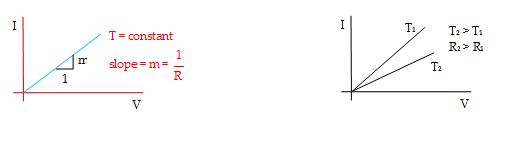

The graph showing the variation between current and voltage is shown in figure.

On the bases of Ohm’s Law the conductors are divided into two catagories

(i) Ohmic Conductors

(ii) Non Ohmic Conductors

Ohmic Conductors

The conductors which obey Ohm’s law are called Ohmic conductors. The resistance of an Ohmic conductor does not depend upon potential difference or current. Metallic conductors like copper, aluminum, iron etc. are the example of ohmic conductors. For such conductors the graph between current and voltage is always a straight line.

Non Ohmic Conductors

The conductors which do not obey ohm’s law are called non-Ohmic conductors. For such conductors, the graph between potential difference and current is not a straight line passing through the origin, e.g. vacuum tubes, semiconductors, etc.

Resistance

Resistance is the property of a substance by which it opposes the flow of current through it.

For a given body, the resistance is defined as the ratio of applied potential difference to the resulting current,

R = \frac{V}{I}

This property of the substance is due to frequent collisions of electrons with the atoms of the conductor.

SI unit of resistance is named ohm (W) which is equivalent to V/A. Its dimensions are

[R] = \left[ {\frac{V}{I}} \right]=\left[ {\frac{{Work/q}}{I}} \right]=\frac{{\left[ {M{{L}^{2}}{{T}^{{-2}}}/\left[ {AT} \right]} \right]}}{{\,\,\,\left[ A \right]}}=\left[ {M{{L}^{2}}{{T}^{{-3}}}{{A}^{{-2}}}} \right]

Reciprocal of the resistance is called conductance (G),

G = \frac{1}{R}=\frac{I}{V}

with dimensions [M-1L-2T3A2]. SI unit of conductance is called Siemens (S), which is equivalent to ohm-1.

Actually resistance R is given by the relation R=\frac{{mL}}{{n{{e}^{2}}A\tau }} as discussed earlier.

This can be written as R=\left( {\frac{m}{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }}} \right)\frac{L}{A} . All quantities in the bracket are microscopic and together form a constant called resistivity denoted by symbol ρ.

Hence resistivity can be written as \displaystyle \rho =\frac{m}{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }}.

Relation Between Resistance R and resistivity ρ

We know that R=\frac{{mL}}{{n{{e}^{2}}A\tau }}

or R=\left( {\frac{m}{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }}} \right)\frac{L}{A} , but \frac{m}{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }}=\rho

therefore

\displaystyle R=\rho \frac{L}{A}

To define the resistivity we take L=A=1 and put it in \displaystyle R=\rho \frac{L}{A}

so we get \displaystyle \rho =R

hence resistivity \displaystyle \rho is equal to the resistance of a conductor of unit length and area of cross section.

Since \rho =\frac{m}{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }} It shows that resistivity depend only on two factors `n’ and `τ’ because m and e are constants

(i)

ρ ∝ \frac{1}{n} [where n = number of free electrons per unit volume which depends on the material of the conductor]

(ii)

ρ ∝ \frac{1}{\tau } [where t = average relaxation time of free electrons in the conductor.]

Variation of Resistivity with Temperature

ρ is independent of the shape and size of the conductor. It depends on temperature.

1.

In case of Ohmic conductors as temperature increases,ρ increases

Explanation

In case of conductors, the number of free electrons is fixed. Due to increase of temperature, the amplitude of vibration of atoms / ions increases. As a result of this, the collisions of electrons with the atoms become more effective and frequent. Therefore, τ decreases and hence ρ increases.

At any temperature t, r is given by the following linear relation with temperature

ρt = ρ0 (1 + αΔT),

where ρ0 = the resistivity at 0°C, and a = temperature coefficient of resistivity.

\displaystyle Also,\alpha =\frac{{({{\rho }_{t}}-{{\rho }_{o}})}}{{{{\rho }_{o}}.\Delta T}}\Rightarrow \text{ }\alpha =\frac{1}{\rho }\,\,\frac{{d\rho }}{{dT}}

Note that the same relations are true for resistance also.

{{R}_{t}}={{R}_{o}}[1+\alpha (T-{{T}_{0}})]

\alpha =\frac{{{{R}_{t}}-{{R}_{o}})}}{{{{R}_{0}}(T-{{T}_{o}})}}

2.

The resistivity of a semiconductor decreases rapidly with increasing temperature.

We can explain these facts from the equation

r = \frac{m}{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }} . . . (i)

In case of insulators and semiconductors, the number of charge carriers at temperature T is given by

n (T) = {{n}_{0}}{{e}^{{-{{E}_{g}}/{{k}_{B}}T}}} . . . (ii)

where Eg is the energy gap between valence and conduction bands in a solid.

Combining equations (i) and (ii),

{{\rho }_{T}} = ρo <sub> {{e}^{{{{E}_{g}}/{{k}_{B}}T}}}

the above relation shows that for semiconductors and insulators, resistivity increases with decreasing temperature.

Important Points To Remember

(i)

At high temperature semi-conductor behaves as conductor R={{R}_{0}}(1+\alpha \Delta T) and \alpha is negative for semiconductor and insulator.

(ii)

Conductivity of electrolytes and liquids will increase with the rise in temperature. In case of electrolytes (and liquids), when temperature is raised,

(a)

the mobility m of the charge carriers increases due to decrease in viscosity,

(b)

the number of charge carriers per unit volume, n, increases due to increase in degree of freedom.

Therefore, the conductivity s (= nem) of electrolytes (and liquids) increases with rise in temperature.

Some Specific Materials

Following are some conducting materials used for specific purposes:

(1)

The filament of electric bulb is made of tungsten which has low resistivity, highMP (3300 K) and gives light at 2400 K.

(2)

The element of heating devices such as heater, geyser, or press is made of nichrome which has high resistivityand high MP.

(3)

Resistances of resistance box, etc. are made of manganin, (or constantan), which has moderate resistivity and is practically independent of temperature.

(4)

Fuse wire is made of copper-tin-lead alloy which has low resistivity and low MP.

Microscopic Form Of Ohm’s Law

we know that I=neAvdhence J=\frac{I}{A}=ne{{v}_{d}}

on putting {{v}_{d}}=\frac{{Ee}}{m}\tau

we get J=ne\frac{{Ee}}{m}\tau =\frac{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }}{m}E

or, J = \frac{E}{\rho } , \because \text{ }\rho \text{=}\frac{m}{{n{{e}^{2}}\tau }}

or, J = σE [ \because s = \frac{1}{\rho } ]

which is the microscopic form of Ohm’s law.

Illustration

If potential difference across a given conductor is kept constant then what is change in drift velocity when the area of cross-section changes by 10%?

Solution:

Current is related to drift velocity as,

\displaystyle I=neA{{V}_{d}}

and V=IR=R\,\,ne\,A{{v}_{d}}\,\,\,\,=\frac{{\rho l}}{A}ne\,A{{v}_{d}}=\rho Ln\,e{{v}_{d}}

So the drift velocity does not change.

Illustration

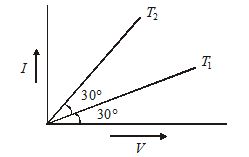

What is ratio of resistance of a given conductor at temperature {{T}_{1}} and {{T}_{2}} with help of following graph?

Solution:

{{R}_{1}}=\frac{1}{{\tan 30{}^\circ }} and {{R}_{2}}=\frac{1}{{\tan 60{}^\circ }}

Therefore \frac{{{{R}_{1}}}}{{{{R}_{2}}}}=\frac{{\tan 60{}^\circ }}{{\tan 30{}^\circ }}=\frac{3}{1}

Illustration

What is the electrical conductivity of a material of length 3m, area of cross-section \mathbf{0}\mathbf{.01}\,\mathbf{m}{{\mathbf{m}}^{\mathbf{2}}} having a resistance of 4\Omega ?

Solution:

As R=\frac{{\rho l}}{A} , and electrical conductivity

\sigma =\frac{l}{\rho } , we have

\sigma =\frac{l}{{RA}}=\frac{3}{{4\times 0.01\times {{{10}}^{{-6}}}}}=7.5\times {{10}^{7}}\,\,oh{{m}^{{-1}}}\,\,{{m}^{{-1}}}

Illustration

A given wire is stretched to reduce its diameter to half its original value. What will be its new resistance?

Solution:

Let {{l}_{1}}= Original length

{{d}_{1}}= Original diameter

{{l}_{2}}= New length

{{d}_{2}}= New diameter

Step- 1: After stretching the wire, volume (or density) of the wire remains the same

i.e., {{A}_{1}}{{l}_{1}}={{A}_{2}}{{l}_{2}}

or, \frac{{\pi d_{1}^{2}}}{4}{{l}_{1}}=\frac{{\pi d_{2}^{2}}}{4}{{l}_{2}}

or, {{l}_{2}}={{\left( {\frac{{{{d}_{1}}}}{{{{d}_{2}}}}} \right)}^{2}}{{l}_{1}}

Since, {{d}_{2}}=\frac{{{{d}_{1}}}}{2}

New length, {{l}_{2}}=4{{l}_{1}}

Step- 2: We know

R=\rho \frac{l}{A}=\rho \frac{{4l}}{{\pi {{d}^{2}}}}

{{R}_{1}}=\frac{{4{{l}_{1}}\rho }}{{\pi d_{1}^{2}}}

and {{R}_{2}}=\frac{{4{{l}_{2}}\rho }}{{\pi d_{2}^{2}}}

\frac{{{{R}_{2}}}}{{{{R}_{1}}}}=\frac{{{{l}_{2}}d_{1}^{2}}}{{{{l}_{1}}d_{2}^{2}}}=\frac{{4{{l}_{1}}d_{2}^{2}\times 4}}{{{{l}_{1}}\times d_{1}^{2}}}=16

New resistance, {{R}_{2}}=16\,\,{{R}_{1}}

Hence, the new resistance of the wire will be 16 times of the original resistance.

Illustration

A copper coil has a resistance of 20.0\,\Omega at 0°C and a resistance of 26.4\Omega at 80°C. Find out the temperature coefficient of resistance of copper.

Solution:

{{R}_{{80{}^\circ C}}}={{R}_{{0{}^\circ C}}}[1+\alpha \,\Delta T]

26.4\Omega =20.0\Omega \,\,[1+\alpha (80-0)]

\frac{{26.4-20}}{{20\times 80}}=\alpha

or \alpha =\frac{{6.4}}{{20\times 80}}=4\times {{10}^{{-3}}}{{({}^\circ C)}^{{-1}}}

Illustration

The resistance of a platinum wire of platinum resistance thermometer at the ice point is

5 W and at steam point is 5.39 W. When the thermometer is inserted in a hot bath, the resistance of the platinum wire is 5.795W. Calculate the temperature of the bath.

Solution:

Rt = R0 (1 + at)

or Rt-R0 = R0αt . . . (i)

Also, R100 = R0 (1 + 100 a)

or, R100 – R0 = 100 R0a. . . .(ii)

Dividing equation (i) by equation (ii)

\frac{{{{R}_{0}}\alpha t}}{{100{{R}_{0}}\alpha }}=\frac{{{{R}_{t}}-{{R}_{0}}}}{{{{R}_{{100}}}-{{R}_{0}}}} x 100

or, t = \frac{{5.795-5}}{{5.23-5}}\times 100 = 345.65°C.

Illustration

A wire has a resistance R. What will be its resistance,

(a)

if it is doubled on itself,

(b)

if it is stretched so that

(i) its length is doubled

(ii) its radius is halved ?

Solution

For a wire,

R = r \displaystyle \frac{L}{S}=\rho \frac{L}{{\pi {{r}^{2}}}}

If its dimensions are changed without changing its mass, its volume remains constant,

V = V’ or SL = S‘L’

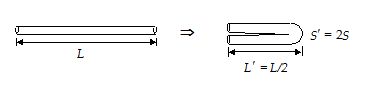

(a)

When the wire is doubled on itself, its length is halved and its area of cross-section is doubled.

S x L = S´ x (L/2) or S’ = 2S

R’ = \displaystyle \rho \frac{{L’}}{{S’}}=\rho \frac{{\left( {L/2} \right)}}{{\left( {2S} \right)}}=\frac{1}{4}\rho \frac{L}{S}=\frac{1}{4}R

(b)

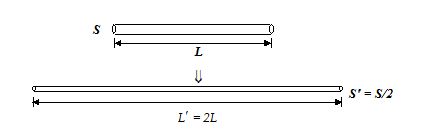

(i) When the length of the wire is doubled by stretching it,

S x L = 2L x S’ or S’ = S/2

R’ = r \displaystyle \frac{{L’}}{{S’}}=\rho \frac{{2L}}{{S/2}}=\rho \frac{{4L}}{S}=4\rho \frac{L}{S}=4R

(ii)

When the wire is stretched so as to reduce its radius to half (r¢ = r/2), we have

S’ = πr’2 = π(r/2)2 = πr2/4 = S/4

From S x L = S’ x L’ = (S/4) x L’

L’ = 4L

R = r \displaystyle \frac{{L’}}{{S’}}=\rho \frac{{\left( {4L} \right)}}{{\left( {S/4} \right)}}=16\rho \frac{L}{S}=16\,R

Illustration

(a)

At what temperature would the resistance of a copper conductor be double of its value at 0°C.

(b)

Does this same temperature hold for all copper conductors, regardless of shape and size?

(aCu = 4.0 x 10-3/C°)

Solution

(a)

The resistance of a wire varies with temperature according to the relation

R = R0(1 + αΔθ)

So \displaystyle \frac{{{{R}_{2}}}}{{{{R}_{1}}}}=\frac{{{{R}_{0}}\left[ {1+\alpha \left( {{{T}_{2}}-0} \right)} \right]}}{{{{R}_{0}}\left[ {1+\alpha \left( {{{T}_{1}}-0} \right)} \right]}}=\frac{{\left( {1+\alpha {{T}_{2}}} \right)}}{{\left( {1+\alpha {{T}_{1}}} \right)}}

Here, R2 = 2R1 and t1 = 0

so 2 = 1 + aT2 or t2 = 1/a = 1/(4 x 10-3) = 250°C

(b)

As here T2 = (1/a), does not include dimensions of the conductor (L and S), it is valid for all copper conductors whatever be their shape and size.